Warning: Attempt to read property "ID" on null in /home/geghna/ethiopianism.net/wp-includes/media.php on line 3125

Notice: Function map_meta_cap was called incorrectly. When checking for the

read_post capability, you must always check it against a specific post. Please see Debugging in WordPress for more information. (This message was added in version 6.1.0.) in /home/geghna/ethiopianism.net/wp-includes/functions.php on line 6121[media id=447 width=320 height=300]

After the Eritrean independence war ended in 1991, Eritreans threw themselves into reconstructing the country’s shattered infrastructure, with whole villages helping out to build small dams, terrace-eroded hillsides, and plant thousands of trees. Photos by Dan Connell.

Once a revolution is over, how do you judge its success? A victory for Mao’s vision of the People’s Republic of China was not exactly a victory for the people of China. A glorious, clean revolution isn’t easy. Look at Russia, France, Cambodia, Iran. Look at Egypt today. In the coming decades, we will see the result of revolutions played out across the Arab world and, quite possibly, across Europe as well. Will they be deemed successes by anyone other than the victors?

A crucial, but little reported, example of a hard fought revolution and its troubling aftermath can be found in the Horn of Africa.

Twenty years ago, Eritrea—in the northeast of Africa—became a legally independent nation, having won its de-facto independence from Ethiopia two years earlier, in 1991. This independence was the end result of a 30-year war with Ethiopia. The revolutionaries who won the war were heroes, champions of freedom standing up against an oppressive, murderous Ethiopian regime backed by the Soviet Union and tacitly supported by the West. They had reestablished an independent Eritrean nation and the future looked bright. But revolutionary opposition and day-to-day power are two totally different things. Once you’ve gotten used to glorious victories, the thrills of red tape and responsibility may well be lost on you. As such, creating a free and democratic society is a total pain in the ass.

Eritrea had been an Italian colony since 1890, Ethiopia since 1935. After the Second World War, Eritrea became part of Ethiopia but maintained a measure of independence. In 1962, and in contravention of a UN resolution, Ethiopia annexed Eritrea. The UN and other world powers looked on, unwilling to jeopardize their relationship with the strategically-vital Ethiopia. As John Foster Dulles, who would go on to be the United States’ secretary of state, said in 1950, “From the standpoint of justice, the opinions of the Eritrean people must receive consideration. Nevertheless, the strategic interest of the United States in the Red Sea basin and considerations of security and world peace make it necessary that the country has to be linked with our ally, Ethiopia.” Eritrea had been screwed.

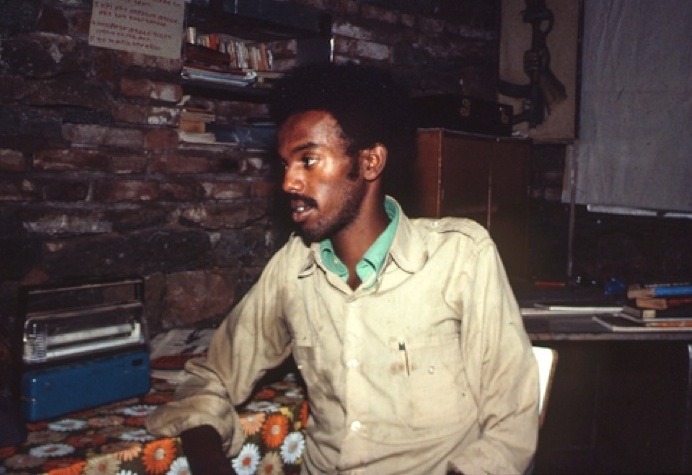

An EPLF member outside Asmara, 1979.

When Eritrea gained its independence in the early 1990s, it was the Marxist revolutionary group The Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) that took power in Asmara, the nation’s capital, having fought a long and hard guerrilla war against Ethiopia. With their ruthless discipline, encouragement of abstinence and collective focus, the EPLF were—in the words of one leading Eritrean historian—“the most successful liberation movement in Africa.” They were tough, and while their intolerance of dissent galvanized their fighting potential, it merely made them tyrants once they were in power.

Led by Isaias Afewerki, they continued their flair for strong, Marxist-sounding names by becoming the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ). And, with Isaias front and center, the PFDJ has remained in power ever since independence.

Today, criticism of the government is not tolerated. Only four religions are officially recognized. Worship in any other church and you’ll be persecuted. There is no civil society to speak of and, every month, kids cross the border to escape national service, which has no fixed end and is essentially a form of government-sponsored slavery. The United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) estimates the number of fleeing Eritreans at 1,000 a month (it’s worth noting that escaping means going through the Sahara into mine-strewn Ethiopia while avoiding being shot by border guards). Reporters Without Borders ranks Eritrea 178th out of 178 in the world for press freedom, which basically means anything approaching journalism is banned.

A UN-supplied refugee camp near the border of Ethiopia, accommodating some of the thousands of Eritreans who flee across the border every year.

By 2012, hundreds of thousands of young Eritreans had fled the country to escape the deepening political repression and to avoid what had become open-ended national service in both the armed forces and state and party-controlled businesses. Three hundred refugees were showing up in Ethiopia each month and being placed in UN-supplied camps near the border.

In May, to coincide with Eritrea’s 20th anniversary celebrations, Amnesty International released a damning report entitled Eritrea: 20 Years of Independence, but Still No Freedom. The report claims that there are, at minimum, 10,000 prisoners being held illegally without trial in Eritrea. The human rights organization’s Eritrea researcher, Claire Beston, told me that this figure did not include those people jailed for “avoiding national service or trying to flee the country.” The report is littered with the testimony of people who have been affected by the actions of the government:

“I last saw my father at the beginning of 2007, they took him away from our house. I know nothing about what happened afterward.”

“This generation, everyone has gone through the prison at least once. Everyone I met in prison has been in prison two or three times.”

“Everybody has to confess what he’s done. They hit me so many times… Many people were getting disabled at that military camp. During the night they would take them to a remote area, tie them up, and beat them on their back.”

There are many more like this. It’s not exactly light summer reading.

The 1984 to ’85 African famine put Eritrea’s war for independence on hold as the liberation front trucked aid into the country to prevent both mass starvation and a wholesale exodus from the contested areas. Ethiopia sought to isolate the Eritreans using food as a weapon.

Tesfamichael Gerahtu, Eritrea’s ambassador to the UK and Ireland, told me that while Eritrea have “some challenges in human rights,” there “are no people incarcerated on the basis of their political beliefs.” The Eritrean Ministry of Foreign Affairs released an angrily-worded response that rejected Amnesty’s “wild accusations.” The release concluded that Amnesty would ignore the 20th anniversary celebrations, “smug in its selfrighteous belief that it can, with impunity, attack and denigrate a young nation, which despite many odds, manages to progress and improve the lives of its citizens.”

Amnesty’s Claire Beston told me that Eritrea’s refusal to acknowledge its illegal detention of its own people was “incredibly disappointing for the families of those affected.” Additionally, she pointed out that Eritrea’s imprisonment of innocent people was in direct contravention with a number of international treaties it had signed up to. Drawing parallels with another country known for imprisoning innocent citizens, the human rights activist Khataza Gondwe has referred to Eritrea as “Africa’s North Korea.”

Eritrea, then, has not become the country many hoped for. “I don’t think there is anyone who doesn’t believe that promises were betrayed,” Eritrean exile Gaim Kibreab—a university professor and author of Eritrea: A Dream Deferred—told me. Kibreab left Eritrea in 1976. For him, the actions of the current government “affect us all. I have relatives in Sudanese refugee camps. I have dear friends in prison in Eritrea.” The deferred dream of a free Eritrea was not just Kibreab’s, but one shared by many of his countrymen, though possibly not Isaias Afewerki and his revolutionary army.

Kibreab wishes for a pluralist democracy in which there is a free press and a flourishing civil society. But was this ever going to be a realistic proposition for a group of hardened guerrilla warriors at the end of a 30-year struggle? Decades of uninterrupted power is probably a closer approximation of Isaias’ dreams. He’s said to be full of contempt for humanity, to be a big drinker and a mean drunk. He’s a human rights violator and a petty thug who’s known to break bottles over people’s heads once he’s had a few.

As such, being boss probably suits him just fine. His former foreign minister, Petros Solomon, a key fighter and comrade in the revolution, was imprisoned in 2001 for speaking out against the government as part of the G-15 group of dissidents, who wrote an open letter to Isaias denouncing the lack of freedom in Eritrea. Solomon has not been heard from since his imprisonment.

Petros Solomon in an underground bunker in the frontline town of Nakfa, in 1979.

Some ex-revolutionary fighters and other defenders of the Eritrean government are scornful of exiled, “so-called intellectuals” like Gaim Kibreab. They believe that the people who now talk about human rights in Eritrea are hypocrites, people who didn’t fight and stand up for the violation of Eritrean human rights in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. There is still a significant amount of support for Isaias in the Eritrean diaspora. The Eritrean ambassador told me that “you must respect that we have had our human rights violated,” in relation to Ethiopia’s annexing of—and then war with—Eritrea, as well as the international support of Ethiopia.

Kibreab, in a way, agrees with him. He told me that when you talk about Eritrea, you have to talk about Ethiopia, which—secure in its importance strategically to the United States—has continued to run roughshod over Eritrea and, in doing so, has alienated Eritrea from the rest of the world. A world that now regards it as a small rogue state with a potential for Islamism, while viewing Ethiopia as a large, roguish, but vital state—a key ally in the “War on Terror.”

“The international community,” Kibreab pointed out, “has never been charitable to the Eritrean government. But if they moved towards liberal democracy, they’d help themselves.” However, this lack of support is worth remembering, particularly since it has been true ever since John Foster Dulles admitted that Eritrea was to be the victim in an international power game. Freedom from the machinations of foreign powers was one of the driving forces of the revolution. Now, still isolated, Isaias and his government continue to battle on, proudly proclaiming survival in the face of international contempt.

In 1998, the Eritreans went back to war with Ethiopia. The country’s youth were quickly mobilized to go back into the trenches.

The interminable military service, for example, makes some sense in the context of Ethiopian aggression. In 1998, the two countries went to war over a small portion of disputed territory surrounding the barren, rock-strewn town of Badme. The war, which lasted for over two years and resulted in the death of up to 100,000 soldiers, was described as “two bald men fighting over a comb.”

Since the end of the war, Ethiopia has failed to recognize an international court ruling that stipulates that Badme is part of Eritrea. Eritrean government officials have repeatedly told me that if Ethiopia recognized the boundary, they would be ready to make friends with their neighbors. Ethiopia funds many of the strands of opposition in Eritrea and, along with the United States, plays a crucial role in a paranoid narrative put forward by the Eritrean government: that Eritrea’s very existence is under constant threat from dark powers beyond its borders.

There is an element of truth to this, but of course Isaias and his government spin it out for all its worth. As far as propaganda goes, Ethiopia is Isaias’ greatest ally.

An EPLF member outside Asmara, 1979.

What I’m also talking about here, when I talk about Eritrea at 20 years, is the difference between the idealism of revolutionary opposition and the practical day-to-day reality of running a government. After years in the mountains fighting a guerrilla war, how was a revolutionary movement going to smoothly transition into power? Just like with the Taliban in Afghanistan, we’ve seen that life in grizzled, iconic opposition is perhaps not the best preparation for a calm, moral government. In opposition, those around Isaias let him do what needed to be done. There was a sense that he was “our bastard.” But, since then, the bastard has never stopped.

Ex-revolutionaries in Eritrea are often characterized as great drinkers, good talkers, and terrible diplomats. They grew up fighting in a revolutionary struggle, and the intricacies of international diplomacy were not for them. Paranoid and wary of showing weakness, they have punished innocent people for their own failings.

This is the sadness of all revolutionary dreams turned sour: the reality of freedom is never the same as the promise of freedom. It’s unlikely that when the EPLF were fighting for their country’s independence they looked up at that East African sky and thought: We dream that some day we will imprison people without trial, that our people will do anything they can to escape the country, that our youth will be locked into national service and that there will be no such thing as journalism.

Every generation reacts against the previous one, though. Isaias is getting old, and with the post-independence generation now 20 years old, the next few years could see some upheaval, hopefully for the better, in Eritrea.

Follow Oscar on Twitter: @oscarrickettnow

See more of Dan’s work at danconnell.net.

More stories about troubled African countries:

Watch – Ground Zero: Mali

Related articles