The honour was formally bestowed on Nega in a ceremony at the 66th World Newspaper Congress, under way in the Italian city of Torino this week, where more than 1,000 media industry representatives have gathered.

Nega is serving an 18-year jail sentence in Addis Ababa’s notorious Kaliti prison, convicted on trumped-up terrorism charges after daring to wonder in print whether the Arab Spring could reach Ethiopia, and for criticising the very anti-terrorism legislation under which he was charged. Arrested in 2011, he was sentenced on 23 January 2012, and denounced as belonging to a terrorist organisation.

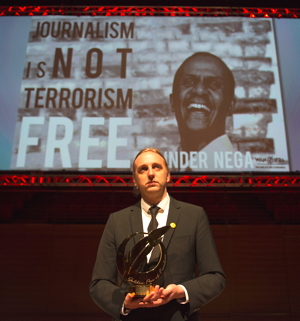

Imprisoned at least seven times in the past decade for committing fearless acts of journalism, Nega is a celebrated intellectual and a relentless fighter for freedom of expression. “Eskinder Nega has become an emblem of Ethiopia’s recent struggle for democracy,” World Editors Forum President Erik Bjerager said, delivering the Golden Penduring the opening ceremony of the World Newspaper Congress and the World Editors Forum in Torino. “No stranger to prison, he is also an unforgettable warning to every working Ethiopian journalist and editor that the quest to create a just, free society comes with a heavy price,” Bjerager said.

Nega’s former prisonmate, Swedish journalist Martin Schibbye, accepted the award on the jailed journalist’s behalf, at the invitation of Nega’s family. He painted a dark picture of life inside Kaliti Prison. “The rooms are more like barns with concrete floors, and it is so crowded that you have to sleep on your side,” he said. “Prisoners are packed likes slaves on a slaveship. Once a month an inmate leaves with his feet first.”

But disease and torture are not the hardest part of life inside Kaliti, according to Schibbye. “It (is) the fear of speaking. It’s not the guard towers with machine guns that keep the prison population calm. It is the geography of fear. People who speak politics are taken away. They disappear.” Schibbye is a freelance journalist who was jailed for 14 months in Kaliti Prison, along with his photographer Johan Persson. They were pardoned and released in September 2012.

“In (Kaliti), fearless people like Eskinder Nega helped the whole prison population to keep their dignity. By still writing. Protesting. Not giving up. He helped us all maintain our humanity. But there is one thing I know that even Eskinder fears. That is to be forgotten,” Schibbye says.

“When you’re locked up as a prisoner of conscience, this is the greatest fear, and the support from the outside is what keeps you going. This Golden Pen Award will not set him free tomorrow, but it will ease his day today. He will go with his head high knowing that he is there for a good cause. That the pain and suffering has a meaning.”

WEF President Erik Bjerager told the ceremony that the world needs to watch the creeping threat of anti-terrorism legislation being used to target journalists. “Ethiopia continues to resort to anti-terrorism legislation to silence opposition and shackle the press. Alarmingly, beyond Ethiopia, countless states around the world are misusing anti-terrorism legislation to muzzle journalists, bloggers and freedom of expression advocates,” Bjerager said. “Research suggests that over half of the more than 200 journalists in jail last year were being held on ‘anti-state’ charges. Let me be clear: Journalism is not terrorism. Politicians should not abuse the notion of national security to protect the government, powerful interests or particular ideologies, or to prevent the exposure of wrongdoing or incompetence.”

Schibbye concluded his acceptance speech, reading from a moving letter penned by Nega to his eight-year-old son. It was smuggled out of Kaliti prison: “The pain is almost physical. But in this plight of our family is embedded hope of a long suffering people. There is no greater honour. We must bear any pain, travel any distance, climb any mountain, cross any ocean to complete this journey to freedom. Anything less is impoverishment of our soul. God bless you, my son. You will always be in my prayers.”

Schibbye told a tearful audience: “When I read these words by Eskinder I know that they will never break him. Because he is in peace with himself. He knows that even though he is chained, robbed of his physical freedom, the freedom to talk or to be silent, the freedom to drink or eat, and even to shit. He knows, as do all prisoners of conscience, that you have it in you to keep the most valuable, the freedom that nobody can take from you, the freedom to determine who you want to be. Eskinder is a journalist. And every day he wakes up in the Kaliti prison is just another day at the office.”

Nine more journalists were jailed in the past month in Ethiopia, as the election campaign started ahead of next year’s poll. “The crackdown was a flashing alarm to the world that no one is safe. That there is a hunting season for journalists in Addis Abeba. But despite this difficult situation, there is light,” Schibbye said.

“Eskinder Nega’s courage has turned out to be contagious; a new generation is stepping up. A generation of young cheetahs have been taking enormous risks writing, tweeting and speaking truth to power, demanding the jailed to be released. It is hopeful. It shows that they can jail journalists but they can never succeed in jailing journalism. Words led Eskinder Nega to the Kaliti prison. And in the end it must also be words that set him free,” Schibbye told a clearly emotional audience.

“When I see this Golden Pen of his, I look back, and think of Eskinder who is left behind in the chaos, on the concrete floor, between walls of corrugated steel I feel sick to the stomach. But then I remember his smile and his strength and I think that at the end of the day, it’s not us that are fighting for his freedom – but rather he who is fighting for ours. Ayzoh Eskinder! Ayzoh! (translation: be strong, chin up).”

Note: The Golden Pen of Freedom is an annual award made by WAN-IFRA to recognise the outstanding action, in writing or deed, of an individual, a group or an institution in the cause of press freedom. Established in 1961, the Golden Pen of Freedom is presented annually and is amongst the most prestigious awards of its kind throughout the world. Behind the names of the laureates lie stories of extraordinary personal courage and self-sacrifice, stories of jail, beatings, bombings, censorship, exile and murder. One of the objectives of the Golden Pen is to turn the spotlight of public attention on repressive governments and journalists who fight them. Often, the laureate is still engaged in the struggle for freedom of expression and the Pen has, on several occasions, secured the release of a publisher or journalist from jail or afforded him or her a degree of protection against further persecution.