By Lorenzo Piccio04 August 2014

Five years ago, during his first visit to sub-Saharan Africa as U.S. president, Barack Obama memorably told Ghana’s parliament that “Africa does not need strong men. It needs strong institutions.” And months before his re-election, Obama stressed strengthening democratic institutions as one of four pillars of his administration’s sub-Saharan Africa strategy .

“Our message to those who would derail the democratic process is clear and unequivocal: the United States will not stand idly by when actors threaten legitimately elected governments or manipulate the fairness and integrity of democratic processes,” Obama said in the strategy.

Obama’s strident and lofty rhetoric on democracy in Africa may make for odd bedfellows this week as 50 African heads of state gather in Washington for the first-ever U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit.

While sub-Saharan Africa as a whole has made marked progress toward democracy and institution building since the 1990s, more than a dozen of the African leaders expected in Washington can aptly be called strongmen — President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda and President Paul Kagame of Rwanda included.

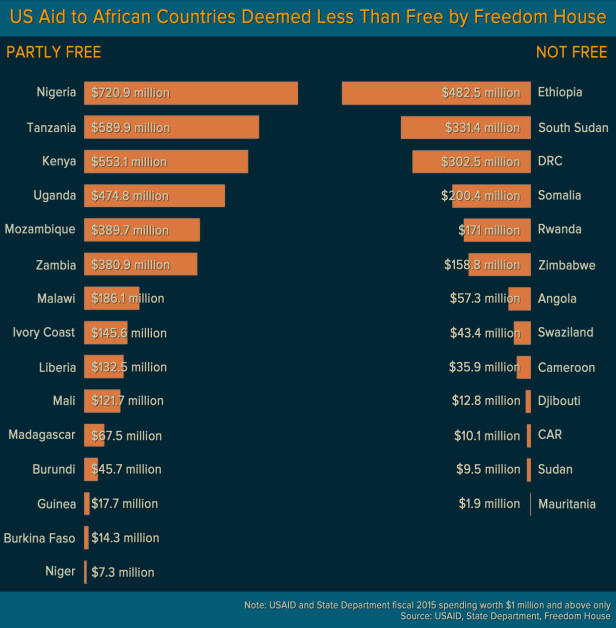

Freedom House classified 20 of 49 sub-Saharan countries as “not free” in its 2014 Freedom in the World index , the think tank’s annual assessment of political rights and civil liberties around the world. Nineteen countries were classified as “partly free,” while only 10 were classified as “free.”

As the graphic above shows, the United States is a significant donor to 28 of those 39 “partly free” or “not free” countries in sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, of the 10 largest U.S. aid recipients in sub-Saharan Africa, only one is rated “free” by Freedom House: South Africa, which is seeing asharp decline in funding under the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

Like administrations before it, the Obama White House has come under fire from some quarters for keeping the aid tap on in countries that routinely trample upon human rights and civil liberties. These advocates argue that the steady flow of U.S. aid money to Africa’s autocrats only prolongs their hold on power.

The prevailing bipartisan view, however, is that it would be foolhardy for the U.S. aid program to tie U.S. foreign aid flows entirely to democracy and human rights considerations. U.S. foreign aid is regarded by many in Washington as a key tool in the U.S. democracy and human rights promotion toolbox — one that can be used to promote and encourage reform not only within the government but also in civil society. Funding civil society groups directly is a strategy routinely employed to avoid giving money to these strongmen.

At the same time, it’s not clear whether the administration or Congress is willing to take the strategic blowback should the United States cut aid to some of its key African partners that happen to have strongmen at the helm.

“The question is how and when to promote democracy when the U.S. has multiple competing national interests. It’s easy to talk about democracy, but what do you do when an ally shows authoritarian tendencies?” said Todd Moss, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development who was deputy assistant secretary in the Bureau of African Affairs at the Bush State Department.

Jennifer Cooke, director of the Africa Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies echoed this sentiment.

“The conundrum is in those countries that are authoritarian but which the U.S. regards as important security partners,” said Cooke, who cited Ethiopia, Uganda and Rwanda as examples.

Below, Devex examines U.S. aid engagement with four authoritarian regimes that are also among the largest recipients of U.S. aid in sub-Saharan Africa: Uganda, Zimbabwe, Rwanda and Ethiopia. In particular, we looked at three key questions that shed light on the administration’s approach to these regimes:

1. To what extent is the Obama administration’s aid engagement tied to progress on democracy and human rights?

2. Is the administration robustly supporting democracy and governance aid programming?

3. Is aid being channeled directly through the government or through nongovernmental channels?

(A previous Devex analysis found that democracy and governance accounted for roughly 5 percent of the Obama administration’s aid spending in sub-saharan Africa.)

Uganda

East Africa’s longest-serving ruler, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has been in power for nearly three decades.

Freedom House rates Uganda as “partly free” in its latest assessment, citing Museveni’s increasingly repressive style of leadership. Critics charge that since abolishing term limits in 2005, Museveni’s “constitutional dictatorship” has persecuted dissidents and militarized the country’s civil institutions. Uganda’s human rights record has deteriorated even further following its passage of a highly controversial law — annulled Friday — that criminalized homosexuality.

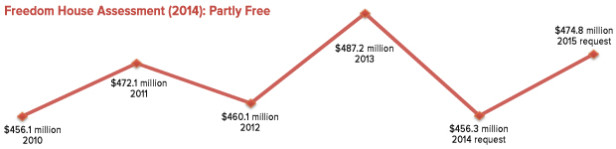

Averaging nearly $470 million over the course of the Obama administration, U.S. aid spending in Uganda had been slated to remain fairly steady in the administration’s fiscal 2015 budget request. Signaling a change in direction, however, the White House announced in June plans to discontinue or redirect funds for “certain additional programs” involving Ugandan government institutions such as the Ugandan Police Force, Ministry of Health and National Public Health Institute. It remains to be seen whether the Ugandan constitutional court’s annulment of the anti-homosexuality law will prompt the administration to reevaluate its decision.

Devex analysis reveals, however, that only 1 percent of USAID local spending in Uganda flows through the Ugandan government — reason to believe that the impact of the announcement on the Ugandan government may be minimal.

In contrast to many other major donors to the East African country, the United States has historically refrained from channeling budget support to Kampala, which helps explain whyUSAID did not suspend aid to Uganda in the wake of a high-profile aid embezzlement scandal back in 2012.

The vast majority of U.S. aid spending in Uganda is coursed through PEPFAR. While USAID’scountry strategy for Uganda elevated democracy and governance as one of three key objectives for the agency’s programming in the East African country, the sector will account for only 1 percent of U.S. aid spending in fiscal 2015, which is down from 2 percent in 2010. In the run-up to Uganda’s next national election in 2016, however, the Obama administration has revealed plans to bolster its support for political parties and civil society.

Zimbabwe

After a period of power sharing with the opposition, Zimbabwe’s longtime president Robert Mugabe is once again firmly in control in Harare; Mugabe won a seventh term in office in last July’s widely disputed election. Freedom House assessed Zimbabwe as “not free,” citing restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly, state-sponsored political violence, as well as serious irregularities in the July 2013 election. At the helm of one of Africa’s most repressive regimes, Mugabe has been in power since Zimbabwe gained independence in 1980.

Early on in his administration, Obama had pledged $73 million in fresh assistance to Zimbabwe — an olive branch to the then months-old power-sharing government. That same year, USAID also reinitiated programming in agriculture and economic growth, which had been on hold for much of the decade. USAID Zimbabwe had redirected the vast majority of its resources toward humanitarian programming in the aftermath of Mugabe’s systematic expropriation of white-owned farms in the early 2000s.

Until recently, the Obama administration had also begun to channel aid to select ministries aligned with the opposition and its leader, then-Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai — further evidence of a thaw in aid relations between the United States and Zimbabwe. According to Cooke, U.S. assistance to the public sector in Zimbabwe has been largely limited to health, particularly HIV prevention and treatment, as well as education.

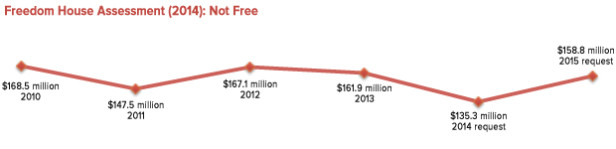

Now that Mugabe has tightened his grip on power once more, the Obama administration, by most accounts, appears to have pulled back on the U.S. aid program’s reengagement with Harare. Very little of the administration’s robust $159 million aid budget for Zimbabwe in fiscal 2015 — which is on a par with recent levels — will likely be channeled through the central government. But the administration has left the door open to continued aid engagement with reform-minded institutions, including the parliament.

Strikingly, the share of U.S. aid to Zimbabwe directed to democracy, human rights and governance is on course to decline even further to just 7 percent in fiscal 2015, compared with 12 percent in fiscal 2010. According to the Obama administration, its programming in the sector will now be focused on safeguarding democratic gains made during the power-sharing period, including the new constitution that was overwhelmingly approved by Zimbabweans in a March 2013 referendum.

Rwanda

Since assuming the presidency in 2000, Paul Kagame has presided over Rwanda’s rapid development progress — no small feat for a small, landlocked country devastated by genocide only two decades ago. At the same time, the African strongman has come under intense criticism from human rights groups for his authoritarian — some would say, repressive — style of leadership. Freedom House assessed Rwanda as “not free,” citing the country’s flawed electoral process and the Kagame regime’s targeting of human rights organizations.

Despite persistent questions over Kigali’s human rights record, Rwanda has emerged as adarling of Western donors — including its single-largest bilateral donor, the United States — during the past decade. Over the course of the Obama administration, however, U.S. aid flows to Rwanda have declined noticeably — proof perhaps that Kigali’s standing in the U.S. aid portfolio may not be quite where it used to be.

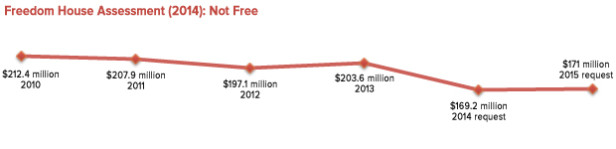

The administration has requested $171 million in foreign aid to Rwanda in fiscal 2015, which is nearly a fifth below fiscal 2010 levels. These cuts appear to have been driven in part by the Obama administration’s reservations over the Kagame regime’s commitment to democracy and human rights. Most notably, in October of last year, the Obama administration announced plans to restrict aid to Uganda’s military over its support for a Congolese rebel group believed to be using child soldiers.

Military aid, however, accounts for only a small portion of U.S. aid to Rwanda, which, much like in Uganda, is mostly in support of PEPFAR programming managed by nongovernmental organizations. Only 3 percent of the administration’s fiscal 2015 aid request for Rwanda has been allocated for democracy, human rights and governance, which is unchanged from fiscal 2010 levels.

Ethiopia

Since taking office upon the death of the Ethiopian strongman Meles Zenawi two years ago, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn has, by most accounts, governed the one-party state with the same iron fist. Freedom House assessed Ethiopia as “not free,” citing the Desalegn government’s harassment and imprisonment of political opponents. Just last month, Addis Ababa came under fire from human rights groups — and lawmakers in Washington — for its detention of Ethiopian opposition leader Andargachew Tsige.

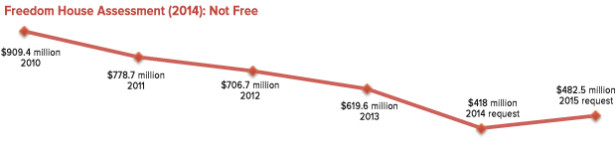

While Addis Ababa remains one of the largest U.S. aid recipients in sub-Saharan Africa, U.S. aid flows to Ethiopia have fallen sharply over the course of the Obama administration. The administration has requested $483 million in foreign aid to Ethiopia in fiscal 2015, down by almost half since fiscal 2010. The vast majority of U.S. aid spending in Ethiopia is channeled toward PEPFAR. U.S. aid officials have said that the budget slashes are part of an effort to transfer PEPFAR resources to countries with higher HIV prevalence.

The Obama administration, on the other hand, is poised to ramp up loans, credits and guarantees for the country’s energy sector. The administration has named Ethiopia as one of six focus countries for its $7 billion Power Africa initiative. With the backing of Power Africa, the Ethiopian government and Reykjavik Geothermal, a U.S.-Icelandic private developer, recently signed a landmark deal to construct a 1,000-megawatt geothermal plant in Corbetti Caldera valued at $4 billion.

Despite the USAID country strategy for Ethiopia’s assertion that democracy and governance is the one sector that has “demonstrably deteriorated,” programming in this area will garner less than 1 percent of U.S. aid spending in Ethiopia in fiscal 2015, which is flat from fiscal 2010. At the same time, there has been little to no indication from the administration that the PEPFAR budget slashes are tied to U.S. concerns over Ethiopia’s democracy and human rights record.

Strikingly, USAID channels roughly a third of its local spending through governmental channels — a share that’s higher than all but five of the agency’s bilateral missions in sub-Saharan Africa. Ethiopia’s harsh NGO laws, which is one of the most restrictive in the world, likely helps explain USAID’s reluctance to channel more funding through nongovernmental organizations.

Check out more insights and analysis provided to hundreds of Executive Members worldwide, and subscribe to the Development Insider to receive the latest news, trends and policies that influence your organization.